One of the key arguments in favor of predictions in sentence comprehension comes from EEG. Prenominal adjectives marked with gender that does not match that of any predictable nouns trigger an ERP effect (often N400-like negativity). This is often referred to as direct evidence for predictions in language comprehension: Only by predicting the noun can the brain “know” already at the adjective which gender is the right one. Below, I refer to this effect as the prenominal prediction effect.

In this series of experiments, I test whether this is a truly predictive effect and what process it reflects.

Experiment 1.

Szewczyk & Schriefers (2013) Journal of Memory and Language

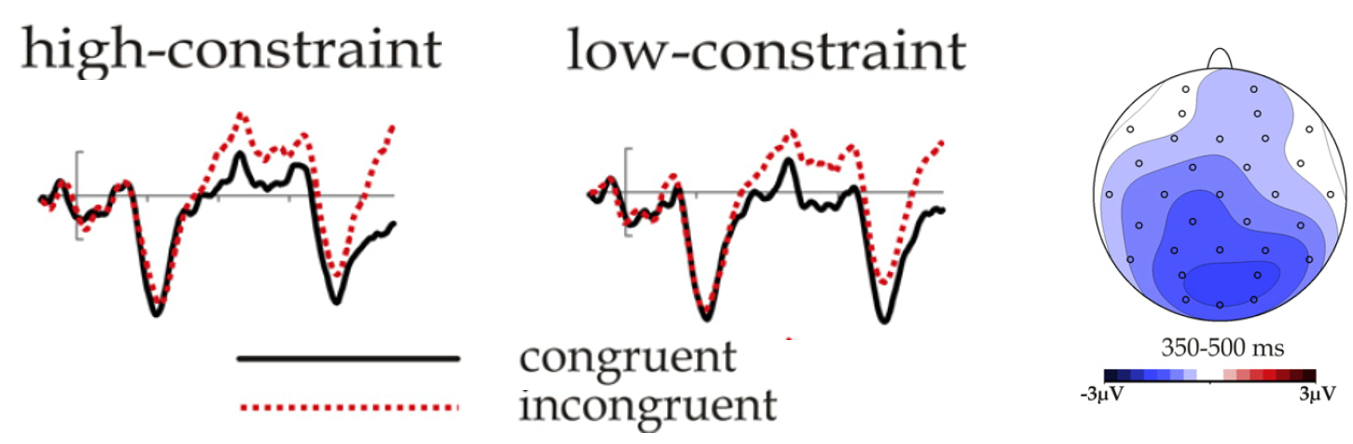

In this paper, we tested whether many nouns can be predicted in parallel. Grammatical gender in Polish also encodes the semantic animacy of the noun. We used stories that most probably could be continued with an animate noun, without making any specific noun predictable (e.g. “For the next party, he invited…”). We tested whether the prenominal prediction effect still occurs in sentences where no specific noun is predictable (they are low-constraint), but the gender of the adjective violates the prediction of animacy.

We found that even when the sentence makes many nouns predictable, and all of them are either animate or inanimate, there is still a robust N400 effect at adjectives mismatching the gender (and animacy) of all the likely nouns. This implied that the brain can predict many nouns in parallel.

Experiment 2.

Szewczyk & Wodniecka (2020) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory & Cognition

[paper] [preprint] [data & code]

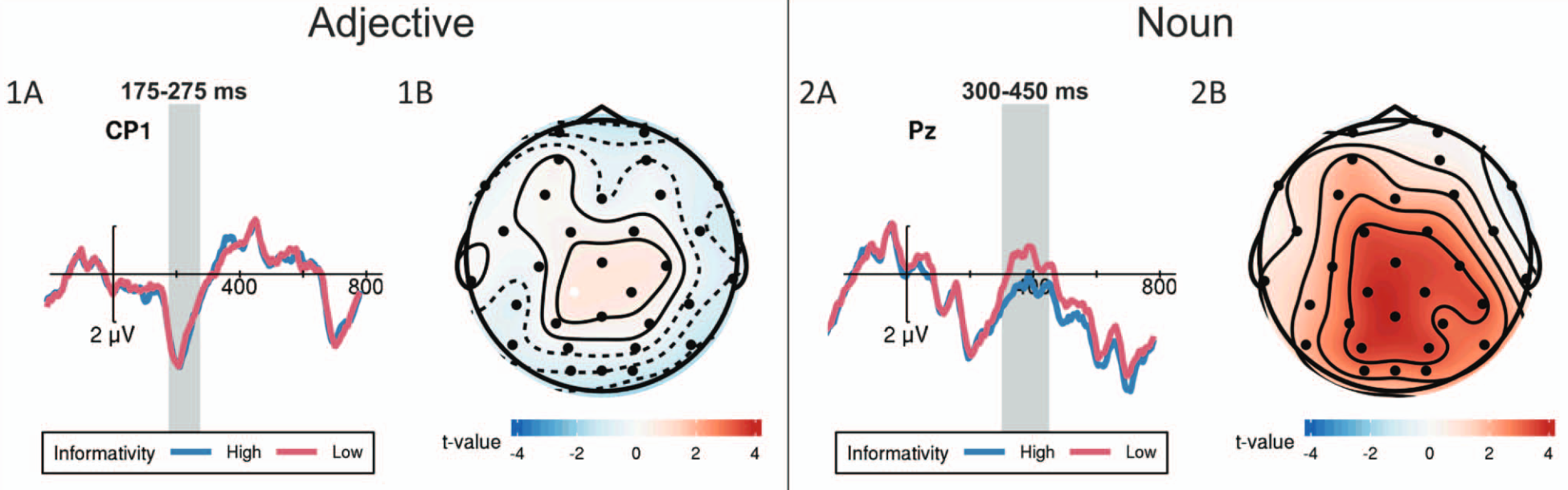

We tested whether the prenominal prediction effect at adjectives reflects updating predictions about the noun. In all the (Polish) items, sentences made at least a few nouns likely candidates. We manipulated how informative the adjective was about the upcoming noun. For more informative adjectives, the gender narrowed down the likely noun candidates significantly, often to just one, while less informative adjectives did not restrict the pool of nouns as much. We also included a condition where adjective’s gender mismatched all likely nouns, as in the first study.

We found that the adjectives strongly impacted the N400 response to the nouns, with more informative adjectives leading to more attenuated N400. Surprisingly, there was no difference in the N400 response to more and less informative adjectives themselves. However, adjectives whose gender mismatched all likely nouns due to animacy differences induced a strong N400.

This paradox was resolved in the subsequent study.

Experiment 3.

Szewczyk, Mech & Federmeier (2021) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory & Cognition

[paper] [materials & code] [data]

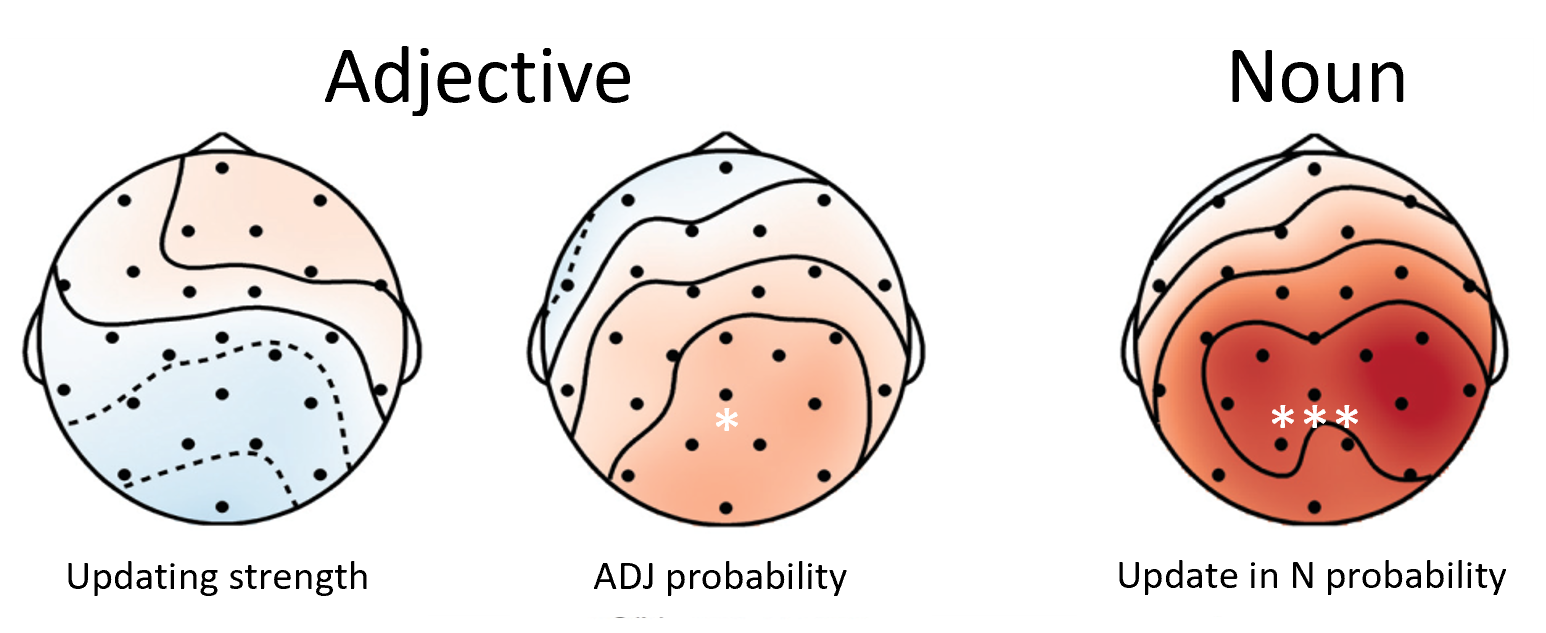

We investigated whether adjectives preceding a noun can semantically update predictions about that noun. We used sentences (in English) with two likely nouns, preceded by adjectives that biased towards either of the two nouns (e.g., “He threatened the other driver with a civil/loaded lawsuit/gun). In this way, the adjective could either increase the probability of one noun at the expense of the other.

We observed that the N400 response to the noun closely mirrored the changes in its probability induced by the adjective, covering both increases and decreases. However, the N400 to the adjective remained unchanged, irrespective of the degree or direction of probability change. Notably, the N400 response to the adjective was influenced by its own probability in the sentence.

Therefore, this study echoed the paradoxical findings of the previous one, demonstrating that adjectives seem to update noun predictions (this time through semantic rather than grammatical cues), yet the process of updating is not detectable.

Conclusions

In sum, the findings seem paradoxical: Adjectives seem to be able to modulate the amplitude of the N400 response to a noun, either through grammatical (Szewczyk & Wodniecka, 2020) or semantic (Szewczyk, Mech & Federmeier, 2021) cues, yet there is no trace of any updating process at the adjectives themselves. Conversely, a significant N400 is observed at the adjective when no probable noun matches its gender.

In our work (Szewczyk, Mech & Federmeier, 2021), we proposed a resolution to these findings:

- The “prenominal prediction effect” at the adjectives is predictive only in a very specific sense: it reflects the contextual facilitation of certain semantic features. For example, when only animate nouns are predictable, features related to animate objects are facilitated. When an adjective with clearly inanimate features (e.g., due to its gender) is then presented, it elicits an N400, indicating access to (yet unactivated) inanimate semantic features. This pattern was observed with animacy-violating adjectives in Experiments 1 and 2, and with low-probability adjectives in Experiment 3.

- Adjectives do not actively update predictions about the upcoming noun. Instead, before encountering the noun, the adjective is retained in semantic working memory.

- Once the noun is encountered, the adjective guides semantic access to the noun, with access being shaped by both the preceding context and the adjective itself.